Cultural geography, like any discipline, evolves over time. And in our time, big changes are happening. Perhaps unimaginable even five years ago, our leaders now align with authoritarian ideas, CEOs engage in fascist salutes, and media influencers platform conspiracy to their publics. The terms of our era have been defined: it is ‘culture’ that has become the battleground on which our futures are forged. ‘Culture wars’ have been transformed from easily-dismissed ‘clickbait’ into the defining conflict of our age.

These changes require cultural geography to respond: to demonstrate that its approaches not only identify these phenomena, but also provide the conceptual framing to understand and appropriately engage with them. This is a vitally important task as contemporary change directly influences the traditional foci of the subdiscipline: the places in which we live, the cultural identities we seek to maintain, and the bodies we wish to protect.

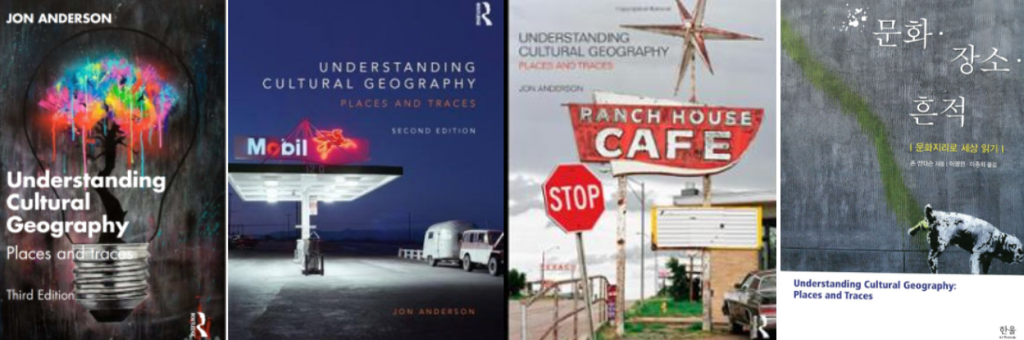

I have written extensively on these issues including the textbook Understanding Cultural Geography which offers a comprehensive introduction to this vital area of human life. There have been three English language editions of this book, and one in Korean (the preface to the third edition can be found here: 0001 Forwards!), and a further extract is also archived here. ).

When introducing students to the central imperatives of cultural geography, I often turn to the following words spoken by British artist Anthony Gormley to a documentary camera on the streets of London:

“I just want […] people to come out here and look at the city that many of them will live in anyway and really look at it; we are not like animals, the victims of an already ordained order, we make this world, and we can’t pretend that we are somehow not responsible for it. We are. Every single bit of it” (in Kidron, 2007, emphasis in original).

In this statement Gormley suggests how, from his perspective, we are part of the world we live in, and if we pay attention we can appreciate our capacity to contribute to that world in a whole manner of ways. For me, this sentiment resonates strongly with the purpose and politics that are imperative for cultural geography. Despite spatial and cultural currents coursing through many subject areas, and which may suggest new interdisciplinary connections in the future (see Anderson, 2025), the ‘unique selling point’ of cultural geography remains vitally significant: our subdiscipline compels us to ‘really look’ at the relations between people, cultural practices, and places, and consider how these entities/processes are not simply assembled together (see for example Delanda, 2006), but often converged in their constitution (see, for example, Anderson, 2012). From this perspective, and through sensuous and rigorous engagement, a cultural geographer must then detect how the ideas and actions of different groups can at once culturally order and geographically border (or (b)order, after Anderson, 2021) our world.

Gormley’s words thus provide a useful reminder that as citizens we should not consider ourselves as passive recipients of inherited prejudices and indifference, but rather transformative agents who can firstly understand and acknowledge (b)orders, and secondly, challenge them. Indeed, in our professional role, we have a distinct responsibility to do something for the cultural geographies that we study and contribute to. Manifesting this responsibility can come in many forms. Perhaps the core responsibility for cultural geographers was articulated a generation ago by Yi Fu Tuan when he said:

“The special calling of cultural geographers [is to] come up with an idea or two that help people see themselves and the world in a slightly different light” (2004: 733).

Cultural geographers are in the business (and that term is adopted advisedly) of ideas – both harnessing others’ and generating our own. Cultural geography mobilises ideas with intent to influence how places and our relation to them can be considered, offering both critique and also inspiration for possible futures. As we consider this, our interdependence with the wider world reminds us that this core responsibility is not neutral, apolitical, or in any way ‘soft’ in its nature. As scholarly labour works to rebuild ‘public’ universities from the metaphorical ruins of ivory towers (Fuller, 2008), our ideas connect with trenches of an array of cultures and campaigns. Our orientations, language choices, theoretical positionings, and products inevitably position our work alongside particular ideas, groups, and places, both within the academy but also beyond it. Our work reinforces particular identity positions, bodies, activities, and sets of power relations, whilst challenging others. As such, the ideas we engage with should help to clarify, communicate, and call out the world’s (in)equalities. To work in cultural geography is therefore to acknowledge the responsibility that academia is a form of activism.